Ampere (Ampe) Explained: The Complete Guide to Understanding Electric Current

Category: Electrical Engineering / Safety Standards

What is an Ampere and Why Does It Matter?

Quick Definition

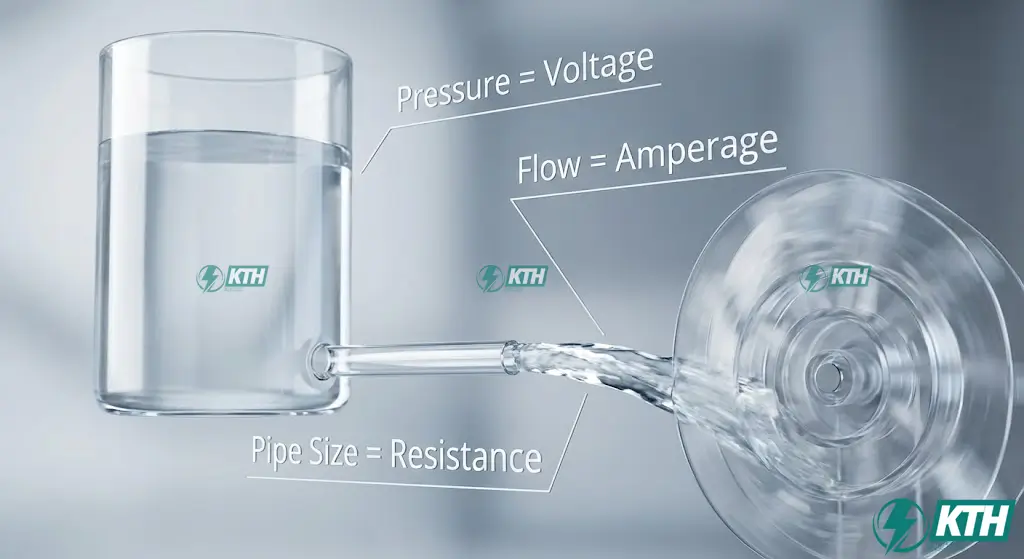

The Ampere (Amp) is the base unit of electric current, representing the flow of electrons. Imagine electricity as water: Volts are the pressure, and Amps are the volume of water flowing per second.

Imagine you are standing next to a massive river. You can see the water rushing past you with incredible force. In the world of electricity, the Ampere (often shortened to Amp) is the measure of that “rushing water”—the actual volume of electric charge flowing through a circuit at any given moment.

If you have ever tripped a circuit breaker in your home after turning on a hair dryer and a vacuum cleaner at the same time, you have experienced the reality of amperage firsthand. It wasn’t the voltage (pressure) that shut your power off; it was the excessive flow of current—too many amps trying to squeeze through a wire not built to handle them. For complex industrial setups, understanding these loads is a key part of our electrical system assessment services.

As an electrical engineer with over two decades of field experience, I can tell you that understanding the Ampere is not just for physicists. Whether you are a homeowner in Ho Chi Minh City trying to choose the right air conditioner, or a facility manager in North Carolina sizing a new industrial motor, grasping the concept of amperage is critical for efficiency, cost savings, and, most importantly, fire safety.

In this comprehensive guide, we will strip away the complex academic jargon and explain exactly what an ampere is, how it relates to volts and watts, and how to use this knowledge to keep your electrical systems running safely.

Brought to you by KTH Electric Co., Ltd. – Your trusted partner in industrial and residential electrical solutions.

VN Address: 251 Pham Van Chieu, An Hoi Tay Ward, Ho Chi Minh City | Hotline: 0968.27.11.99

US Address: 2936 Pear Orchard Rd, Yadkinville, NC 27055 | Hotline: 1 (336) 341-0068

Email: kthelectric.com@gmail.com

The Physics Behind the Ampere (Deep Dive)

To truly master electrical safety, we must look beneath the surface. While we often treat electricity like a utility, it is, at its core, a physical phenomenon involving the movement of subatomic particles.

The Scientific Definition

Technically, the Ampere (Symbol: A) is the International System of Units (SI) base unit for electric current.

In May 2019, the scientific community redefined the ampere. It is now defined by taking the fixed numerical value of the elementary charge ($e$) to be $1.602176634 \times 10^{-19}$ when expressed in the unit Coulomb (C).

The Electron Flow

Current is simply the flow of electrons. One Ampere represents one Coulomb of electrical charge moving past a specific point in a circuit in one second.

Specifically, for 1 Amp of current to flow, approximately $6.24 \times 10^{18}$ electrons must pass a single point every second.

Visualization: When you look at a standard 10A fuse, imagine it as a traffic cop designed to stop the flow if more than 62 quintillion electrons try to rush past it per second. Any more than that, and the friction (resistance) generates enough heat to melt the wire—or the fuse blow to save it. This principle is fundamental to how protective devices like a recloser operate in larger distribution networks.

A Tribute to History: The unit is named after André-Marie Ampère (1775–1836), a brilliant French mathematician and physicist who is considered one of the fathers of electrodynamics. He was the first to demonstrate that a magnetic field is generated when two parallel wires carry electric current—a principle that allows every DC machine and electric motor in your factory or home to function today.

Volts vs. Amps vs. Watts vs. Ohms: The Water Analogy

The relationship between these four units is the foundation of all electrical engineering. At KTH Electric, we use the “Water Tank Analogy” to explain this to clients, as it instantly clarifies how electricity behaves.

1. Voltage (V) = Water Pressure

Voltage is the force pushing the electrons. A tank filled higher with water has more pressure (higher voltage) at the bottom.

- Vietnam Standard: 220V (High pressure).

- US Standard: 120V (Lower pressure).

2. Amperage (A) = Water Flow Rate

Amperage is the volume of water flowing through the hose per second. A wide hose allows a lot of water (High Amps); a thin straw allows very little.

Key Insight: It is the flow (Amps) that fills your bucket (does the work), not just the pressure.

3. Resistance (Ohm / Ω) = The Size of the Hose

Resistance is anything that restricts the flow. A thin wire has higher resistance than a thick cable. Forcing high amps through a thin wire causes friction (heat), potentially leading to fire.

4. Wattage (W) = Total Power

Wattage is the total work done. Think of a water wheel spinning at the end of the hose. Its speed depends on both pressure (Voltage) and flow (Amperage).

Formula: Watts = Volts × Amps

Essential Ampere Formulas for Electrical Engineers

Whether you are troubleshooting a control panel in Yadkinville, NC, or designing a lighting system in Ho Chi Minh City, you cannot guess with electricity. You must calculate. You can find more detailed questions and answers on these topics in our electrical engineering interview questions section.

Ohm’s Law

Current (Amps) = Voltage (Volts) / Resistance (Ohms)

Application: Battery voltage (12V) / Bulb resistance (2Ω) = 6 Amps.

DC Power Formula

Current (Amps) = Power (Watts) / Voltage (Volts)

Application: 100W light / 12V = 8.33 Amps.

AC Single Phase

PF = Power Factor (Efficiency)

Application: 2000W Heater (220V) = ~9.09 Amps.

AC Three Phase

Used for industrial motors.

For variable loads, understanding overload relays is essential.

Conversion Cheat Sheet: Amps to Watts, kW, and HP

One of the most frequent questions we receive on our hotline (0968.27.11.99) is: “I have a 2HP motor; what size breaker do I need?” Consumers speak in Watts or Horsepower, but electricians speak in Amps. For precise industrial applications, we often recommend our motor monitoring solutions to track these metrics in real-time.

Here is a quick reference guide to bridge that gap.

Watts to Amps (at 220V – Vietnam Standard)

- 100 Watts (Light Bulb): $\approx 0.45 \text{ Amps}$

- 1000 Watts (Iron/Small Heater): $\approx 4.5 \text{ Amps}$

- 2000 Watts (Electric Kettle): $\approx 9.1 \text{ Amps}$

- 3500 Watts (Instant Shower Heater): $\approx 16 \text{ Amps}$ (Requires 2.5mm² or 4.0mm² wire)

- 5000 Watts (Central AC): $\approx 22.7 \text{ Amps}$

Watts to Amps (at 120V – US Standard)

- 100 Watts: $\approx 0.83 \text{ Amps}$

- 1000 Watts: $\approx 8.3 \text{ Amps}$

- 1500 Watts (Space Heater): $\approx 12.5 \text{ Amps}$ (This is why space heaters often trip standard 15A breakers in US homes).

Horsepower (HP) to Amps (Approximate)

Note: This varies based on motor efficiency and power factor.

- 1 HP (Single Phase 220V): $\approx 5 – 7 \text{ Amps}$

- 1 HP (Single Phase 110V): $\approx 10 – 14 \text{ Amps}$

- 10 HP (Three Phase 380V): $\approx 15 – 17 \text{ Amps}$

How to Measure Amperage Safely

As an engineer, I cannot stress this enough: You cannot see electricity, but it can see you. Measuring amperage is inherently more dangerous than measuring voltage because it often involves interacting with the flow of current itself. At KTH Electric, we train our technicians on two primary methods, often used in conjunction with thermal scan electrical cabinet services to detect overheating caused by excess amperage.

1. The Clamp Meter (Ampe Kìm): The Professional’s Choice

For 99% of household and industrial applications, this is the tool you should use.

- How it works: It uses the principle of magnetic induction. Every wire carrying current creates a magnetic field around it. The clamp meter detects this field and calculates the amperage without ever touching the bare copper.

- Why it’s safe: It is “non-contact.” You do not need to cut the wire or shut off the circuit to take a reading.

Step-by-Step Guide for Clamp Meters:

- Isolate the single conductor: You cannot clamp around a standard extension cord containing both the Phase (Hot) and Neutral wires. The meter will read Zero. You must separate the wires and clamp only the Live/Phase wire.

- Set the Dial: Turn the dial to “A~” (for AC current) or “A=” (for DC current).

- Clamp: Open the jaws and enclose the wire. Ensure the jaws close fully.

- Read: The display shows the amperage flowing in real-time.

2. The Digital Multimeter (VOM): The Series Method

- How it works: You must physically break the circuit and place the multimeter in series, meaning the electricity must flow through the meter to get to the device.

- The Danger: If you accidentally connect the meter in parallel (like you do for voltage) while the probes are in the “Amps” jack, you create a direct short circuit. This will instantly blow the fuse inside the meter and potentially cause an arc flash. Do not use this method for measuring mains power (220V/110V) unless you are trained.

Amperage in Daily Life: Wire Sizing and Safety

Why do electrical fires happen? In my forensic engineering work, the most common cause isn’t a “short circuit” in the dramatic movie sense; it’s overloading.

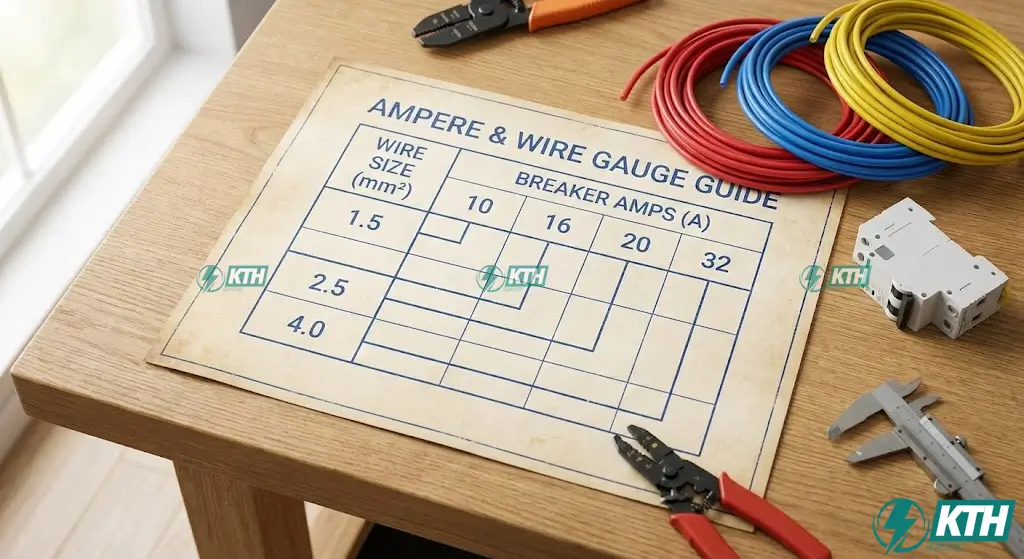

Wire Selection (Vietnam Standards – TCVN & IEC)

Think back to the water pipe analogy. If you try to force a fire hydrant’s worth of water (High Amps) through a drinking straw (Thin Wire), the straw will burst. In electricity, the “bursting” is heat. For larger loads, calculating the correct gauge is critical—you can refer to our guide on wire size for 50A breaker for a specific high-amp example.

Every wire gauge has an Ampacity (Ampere Capacity)—the maximum current it can carry before getting dangerously hot.

- ✅ $1.5\text{mm}^2$ Copper Wire: Safe up to $\approx 16 \text{ Amps}$. Suitable for lighting circuits and fans.

- ✅ $2.5\text{mm}^2$ Copper Wire: Safe up to $\approx 21-27 \text{ Amps}$. The standard for standard wall sockets.

- ✅ $4.0\text{mm}^2$ Copper Wire: Safe up to $\approx 32-35 \text{ Amps}$. Required for air conditioners ($>18000 \text{ BTU}$) and instant water heaters.

The Golden Rule: You must size your wire based on the maximum possible Amperage of the load. Saving money on thinner wire is the most expensive mistake you can make.

Circuit Breakers (Aptomat): The Safety Guard

The job of the circuit breaker (MCB) is to protect the wire, not the appliance. If you have $1.5\text{mm}^2$ wire (rated 16A) but you install a C32 (32 Amp) breaker, you have created a fire trap. If you plug in a heavy load drawing 25 Amps, the breaker won’t trip (because 25 < 32), but the wire will melt (because 25 > 16). For high-voltage protection systems, we also provide recloser maintenance services.

- C16 / C20 Breakers: Standard for bedroom/living room outlets.

- C32 / C40 Breakers: Used for main inputs or heavy machinery.

Battery Capacity: The Ampere-Hour (Ah)

If you look at your smartphone or a solar battery at our KTH Electric projects, you see ratings in mAh or Ah. This is crucial for systems using inverters; if you are experiencing issues, check our guide on Growatt inverter error codes.

Ampere-Hour (Ah): This measures capacity, not flow. It tells you how many Amps the battery can provide for one hour before dying.

Example: A 100Ah Solar Battery.

- It can provide 1 Amp for 100 Hours.

- OR it can provide 10 Amps for 10 Hours.

- OR it can provide 100 Amps for 1 Hour.

DC Amps vs. AC Amps: What is the Difference?

While an Ampere is always $6.24 \times 10^{18}$ electrons, how those electrons move changes the game.

Direct Current (DC)

- The Flow: Unidirectional. Electrons flow steadily from negative to positive.

- Where found: Batteries, Solar Panels, EVs, Electronics.

- Amperage Characteristic: Constant and steady. High DC amperage is notoriously difficult to switch off because it sustains electrical arcs (sparks) much longer than AC.

Alternating Current (AC)

- The Flow: Oscillating. The electrons vibrate back and forth 50 times (Vietnam/Europe) or 60 times (US) per second.

- Where found: The Grid, Household Outlets, Induction Motors.

- Skin Effect: At high frequencies, AC current tends to flow on the outer surface (“skin”) of the conductor rather than through the middle. This is a major calculation factor for the massive busway systems we install in factories.

The “Danger Zone”: How Many Amps Can Kill You?

There is an old saying: “It’s not the volts that kill you, it’s the amps.” This is true, but with a caveat: Voltage is what pushes the amps through your skin. You need high voltage to overcome the body’s resistance to deliver the deadly amperage. Proper insulation monitoring solutions are vital to preventing accidental contact.

Here is the physiological reality of Amperage on the human body (based on IEC 60479 standards):

- ⚡ $0.5 – 1 \text{ mA}$ (Milliampere): Threshold of perception. You feel a slight tingling.

- ⚡ $10 – 20 \text{ mA}$: The “Let-Go” threshold. Your muscles contract involuntarily. If you are holding a live wire, you physically cannot let go.

- ⚡ $50 – 100 \text{ mA}$: Respiratory arrest. The muscles controlling breathing are paralyzed.

- ☠️ $100 \text{ mA} – 200 \text{ mA}$ (0.1 – 0.2 Amps): Ventricular Fibrillation. The heart loses its rhythm and quivers uselessly. Death is almost certain without immediate defibrillation.

- ☠️ $> 200 \text{ mA}$: Severe burns and cardiac arrest. The heart clamps shut tight.

Conclusion

The Ampere is the heartbeat of the modern world. It is the variable that determines whether a motor spins or stalls, whether a wire functions safely or melts, and whether a battery lasts all day or dies in an hour.

For homeowners, understanding amps means knowing why you shouldn’t plug a heater into a cheap extension cord. For facility managers and engineers, precise amperage calculation is the line between operational efficiency and catastrophic downtime.

At KTH Electric Co., Ltd., we live and breathe these calculations. Whether you need a complex load analysis for a factory in Ho Chi Minh City or electrical system upgrades in North Carolina, our team ensures your amperage is managed, monitored, and safe.

Need Help Sizing Your System?

Vietnam: 0968.27.11.99 | 251 Pham Van Chieu, Go Vap, HCMC

USA: 1 (336) 341-0068 | 2936 Pear Orchard Rd, Yadkinville, NC

Email: kthelectric.com@gmail.com

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

A: Think of water. Volts are the pressure pushing the water. Amps are the amount of water actually moving. You can have pressure without flow (plugged hose), but you need flow (Amps) to do real work.

A: In Vietnam (220V), it uses approx. 9 Amps. In the US (120V), the same power requires approx. 16.6 Amps. This is why US plugs are often thicker—they must carry more current for the same power. For specific installation requirements, check out our guides on wiring various receptacles like the NEMA 5-30 or NEMA 6-20.

A: This usually indicates a Short Circuit (massive surge of amps potentially in the thousands) rather than a simple overload. If the breaker trips after a few minutes, it is likely a standard Overload (slightly too many amps for the rating).

A: Ah stands for Ampere-Hour. A 20,000mAh (20Ah) power bank can theoretically deliver 1 Amp of current to your phone for 20 hours, or 2 Amps (fast charging) for 10 hours. Learning essential electrical knowledge can help you understand these ratings better.